History

Melozzo da Forlì, Sixtus IV appoints Bartolomeo

Platina librarian of the Vatican Library

and orders its rearrangement.

ORIGINS

fresco, second half of 15th century. Anonymous,

Sixtus IV visits the sala latina of the Vatican Library

with his nephews and the librarian Bartolomeo

Platina.

FROM NICHOLAS V TO SIXTUS V

publica.

The mid-fourteenth century, after the Popes had returned to Rome with Gregory XI in 1378, is the period which may be thought of as

the beginning of the modern history of the Vatican Library. It was Nicholas V (1447-1455) who decided that the Latin, Greek and

Hebrew manuscripts, which had grown from 350 to around 1,200 from his accession to the time of his death (March 24 1455), should

be made available for scholars to read and study.

The project of Nicholas V was resumed, completed and carried out by Sixtus IV (1471-1484), with a bull (Ad decorem

militantis Ecclesiae, June 15 1475), the nomination of a librarian (Bartolomeo Platina) and the necessary financial support.

The new institution was housed in the ground floor of a building that had already been refurbished by Nicholas V,

with an entrance from the Cortile dei Pappagalli and a façade on the cortile del Belvedere. Sixtus IV had the rooms decorated by some of

the best painters of the time. There were four rooms, respectively called Bibliotheca Latina and Bibliotheca Graeca (for works in these

two languages); Bibliotheca Secreta (for manuscripts which were not directly available to readers, including certain

precious ones); Bibliotheca Pontificia (for the Papal archives and registers). The Librarian was assisted by three aides and by a bookbinder.

Books were read on site under the discipline of strict regulations; but loans were also made, and the records of the books loaned during

the years 1475-1547 are still in existence (Vat. lat. 3964 and 3966). The collection continued to grow, from a total of 2,527 manuscripts

in 1475 to a total of 3,498 in 1481.

Sixtus V approves Domenico Fontana's design for the

new Vatican Library

SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES

In the seventeenth century entire libraries, of princely or private origin, began to be integrated into the collection. Many of these have remained distinct from the open collections which originated in the Library itself and have been made into special, closed collections of manuscripts and printed books: the Palatine library of Heidelberg (1623), the library of the Dukes of Urbino (1657) and the collection of Queen Christina of Sweden (1690). A characteristic of the eighteenth century was the birth and progressive growth in the Vatican Library of sections dedicated to antiquarian and artistic collections. First of all, the Numismatic Department (Medagliere), which was inaugurated in 1738 with the purchase of the collection of Greek and Roman coins and medals gathered by Card. Alessandro Albani, which, at the time, was the largest such collection in the world after that of the King of France. In addition, the Capponi Library was purchased in 1746; and the Ottoboni Library, in 1748. The Museo Sacro (Sacred Museum) was created in 1757 by combining three important collections, and was constantly enriched with various early Christian artefacts (ivories, enamels, bronzes, glassware, earthenware, fabrics, etc.) which mostly came from the Roman catacombs. In 1767, the separation of the secular artefacts from the religious ones brought about the creation of the Secular Museum (Museo Profano). Both Museums have been entrusted to the care of the Vatican Museums since 1999. In 1785 the Collection of Engravings (Gabinetto delle Stampe) was founded. The scholarly eighteenth century also saw the emergence of a project to publish a complete catalogue of the manuscripts which were preserved in the Library. However, of the grandiose series which had been planned by Giuseppe Simonio Assemani and by his nephew Stefano Evodio Assemani, which was meant to include twenty folio volumes, only the first three and an incomplete fourth volumes were ever published.

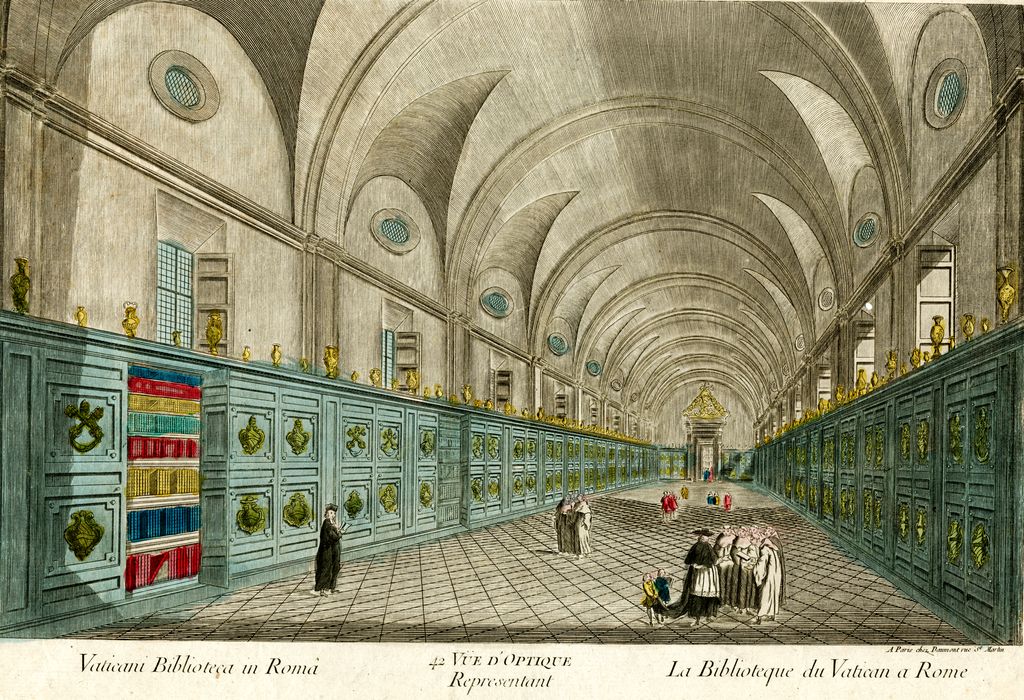

Vedute Vaticano e Roma, pl. 21, etching, 1796.

Francesco Barbazza da Francesco Pannini,

View of the Sistine Hall.

and watercolor, second half of

18th century. Perspective

View of the Vatican Library.

NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURIES

In 1798-99 and in 1809, Rome was invaded and taken by the French and then by the Napoleonic armies. This led to considerable losses, including that of nearly all the numismatic collection which had been gathered up until then. In 1809, however, when Rome was annexed to the French Empire, the Vatican Library was became a National Library and was enriched with the collections of the religious orders. The majority of the manuscript and artistic patrimony that had been taken, was recovered after the Congress of Wien. Between 1825 and 1855, in various phases, the collection of printed books were enriched by the large collection gathered by Leopoldo Cicognara, including art books and antiquities. Under Leo XIII (1878-1903), the Library was opened to a larger public of researchers and historians; in 1892 the current Reading Room for Printed Books was opened, with many books on the open shelves; and the opening hours were lengthened. During this period, which was marked by the tenure of the Jesuit Prefect Franz Ehrle (1895-1914), the card catalogue of printed books was begun, as was the publication of printed manuscript catalogues, produced according to detailed rules which have remained in force to this day. In 1900 the first volume of the Studi e Testi series was published. This period also saw the founding of the Restoration Laboratory, as well as some very important acquisitions. In 1902 the Vatican Library purchased the Barberini Library, which had rivalled it in importance in the seventeenth century, along with the Barberini Archives and the baroque wooden shelving which had contained the volumes when they were at Palazzo Barberini. This collection of more than 11,000 Latin, Greek and Oriental manuscripts and of over 36,000 printed books considerably increased the size of the Library’s collection. In the same year, the library of manuscripts and printed books which had belonged to the Sacred Congregation de Propaganda Fide became a part of the Vatican Library. This collection included the Borgiano collection, rich in manuscripts from various parts of Asia, which had been gathered by Card. Stefano Borgia (1731-1804). The period following the First World War saw the arrival, after various difficulties, of the collection of the bibliophile Francesco De Rossi (over 1,200 manuscripts and around 6,000 rare printed books, including 2,500 incunabula). The Chigi collection arrived in 1923, followed by the Chigi Archives (1944). The Ferrajoli collection, including around 30,000 autographs, arrived in 1926. In 1927, when the introduction of the automobile had rendered the old stables in the Cortile del Belvedere (to one’s right when facing the entrance to the Library), Pope Pius XI (1922-1939) decided to transform them into stacks for the Library’s printed books. In the same period, the financial support of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the collaboration of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. allowed the compilation of a completely new card catalogue of the printed books. During the Second World War the Library, which remained closed for about one academic year (13th July 1943-2nd October 1944), housed a number of book collections, both religious and secular, which were at serious risk of destruction; among these was the library of the Abbey of Montecassino. In 1940, during the Pontificate of Pius XII (1939-1958), the collection of the Archive of the Chapter of St. Peter’s arrived at the Vatican Library. In 1945 arrived the collection of Federico Patetta, which is very important for the history of the Piemonte region and contains a very rich collection of autograph letters. At the beginning of the 1950’s, most of the manuscripts were microfilmed. The microfilms are housed at the Pius XII Memorial Library in St. Louis, Missouri. During the 1970s, in the newly constituted Archival Section (Archival Section) of the Library, the archives of the Barberini and Chigi families were brought in, together with the Archive of the Chapter of St. Peter and of other Roman churches. In 1981, the association American Friends of the Vatican Library was founded to stimulate international interest and support for the institution; the association supports the Library by financing scientific publications and other projects. From 1982 to 1984, with the financial support from the German Episcopal Conference, new stacks were built for the manuscripts underneath the internal courtyard of the Library. With the Prefect (1984-1997) Leonard E. Boyle, manual cataloguing of printed books was definitively replaced with electronic cataloguing; in the following years, the data contained in the old card catalogues has been converted to electronic format. In September 2002 the new Periodicals Reading Room, which holds about a thousand periodicals on open shelf, was opened to the public. Nowadays, the Vatican Library preserves over 180,000 manuscripts (including archival units), 1,600,000 printed books, about 9,000 incunabula, over 300,000 coins and medals, more than 150,000 prints, thousands of drawings and engravings and over 200,000 photographs.

Librarians of the H.R.C.

1501-1555, Bibliothecarius I: 1550-1555

Roberto de’ Nobili

1541-1559, Bibliothecarius II: 1555-1559

Alfonso Carafa

1540-1565, Bibliothecarius III: 1559-1565

Marcantonio Da Mula

1506-1572, Bibliothecarius: IV 1565-1572

Guglielmo Sirleto

1514-1585, Bibliothecarius V: 1572-1585

Antonio Carafa

1538-1591, Biliothecarius VI: 1585-1591

Marcantonio Colonna

1523 ca.-1597, Bibliothecarius VII: 1591-1597

Cesare Baronio

1538-1607, Bibliothecarius VIII: 1597-1607

Ludovico de Torres

1551-1609, Bibliothecarius IX: 1607-1609

Scipione Borghese Caffarelli

1576-1633, Bibliothecarius X: 1609-1618

Scipione Cobelluzzi

1564-1626, Bibliothecarius XI: 1618-1626

Francesco Barberini

1597-1679, Bibliothecarius XII: 1626-1633

Antonio Barberini

1569-1646, Bibliothecarius XIII: 1633-1646

Orazio Giustiniani

1580-1649, Bibliothecarius XIV: 1646-1649

Luigi Capponi

1583-1659, Bibliothecarius XV: 1649-1659

Flavio Chigi

1631-1693, Bibliothecarius XVI: 1659-1681

Lorenzo Brancati

1612-1693, Bibliothecarius XVII: 1681-1693

Girolamo Casanate

1620-1700, Bibliothecarius XVIII: 1693-1700

Enrico Noris

1631-1704, Bibliothecarius XIX: 1700-1704

Benedetto Pamphilj

1653-1730, Bibliothecarius XX: 1704-1730

Angelo Maria Querini

1680-1755, Bibliothecarius XXI: 1730-1755

Domenico Passionei

1682-1761, Bibliothecarius XXII: 1755-1761

Alessandro Albani

1692-1779, Bibliothecarius XXIII: 1761-1779

Francesco Saverio de Zelada

1717-1801, Bibliothecarius XXIV: 1779-1801

Luigi Valenti Gonzaga

1725-1808, Bibliothecarius XXV: 1802-1808

Giulio Maria Della Somaglia

1744-1830, Bibliothecarius XXVI: 1827-1830

Giuseppe Albani

1750-1834, Bibliothecarius XXVII: 1830-1834

Luigi Lambruschini

1776-1854, Bibliothecarius XXVIII: 1834-1853

Angelo Mai

1782-1854, Bibliothecarius XXIX: 1853-1854

Antonio Tosti

1776-1866, Bibliothecarius XXX: 1860-1866

Jean-Baptiste Pitra

1812-1889, Bibliothecarius XXXI: 1869-1889

Placido Maria Schiaffino

1829-1889, Bibliothecarius XXXII: 1889

Alfonso Capecelatro

1824-1912, Bibliothecarius XXXIII: 1890-1912

Mariano Rampolla del Tindaro

1843-1913, Bibliothecarius XXXIV: 1912-1913

Francesco di Paola Cassetta

1841-1919, Bibliothecarius XXXV: 1914-1919

Aidan [Francis Neil] Gasquet

1846-1929, Bibliothecarius XXXVI: 1919-1929

Franz Ehrle

1845-1934, Bibliothecarius XXXVII: 1929-1934

Giovanni Mercati

1866-1957, Bibliothecarius XXXVIII: 1936-1957

Eugène Tisserant

1884-1972, Bibliothecarius XXXIX: 1957-1971

Antonio Samoré

1905-1983, Bibliothecarius XL: 1974-1983

Alfons Maria Stickler

1910-2007, Bibliothecarius XLI: 1985-1988

Antonio María Javierre Ortas

1921-2007, Bibliothecarius XLII: 1988-1992

Luigi Poggi

1917-2010 , Bibliothecarius XLIII: 1994-1997

Jorge María Mejía

1923-2014, Bibliothecarius XLIV: 1998-2003

Jean-Louis Tauran

1943-2018 , Bibliothecarius XLV: 2003-2007

Raffaele Farina

1933- , Bibliothecarius XLVI: 2007-2012

Jean-Louis Bruguès

1943- , Bibliothecarius XLVII: 2012-2018

José Tolentino de Mendonça

1965- , Bibliothecarius XLVIII 2018-2022

Angelo Vincenzo Zani

1950- , Bibliothecarius XLIX 2022-2025

Giovanni Cesare Pagazzi

1965- , Bibliothecarius L 2025-

BIBLIOGRAPHY

b. de rossi, “De Origine Historia Indicibus Scrinii et Bibliothecae Sedis Apostolicae Commentatio”, in h. stevenson Jun., Codices Palatini Latini Bibliothecae Vaticanae descripti, Romae 1886, pp. I-CXXXII.f. ehrle, Historia Bibliothecae Romanorum Pontificum tum Bonifatianae tum Avenionensis, I, Romae 1890.

a. pelzer, Addenda et emendanda ad Francisci Ehrle Historiae [sic] Bibliothecae Romanorum Pontificum tum Bonifatianae tum Avenionensis, In Bibliotheca Vaticana 1947.

j. bignami odier, La Bibliothèque Vaticane de Sixte IV à Pie XI. Recherches sur l'histoire des collections de manuscrits, Città del Vaticano 1973 (Studi e testi, 272).

c.carlen, The Popes and the Vatican Library, Grosse Pointe Farms, Michigan, 1984.

j. mejia - c. granfiger - b. jatta, I Cardinali Bibliotecari di Santa Romana Chiesa, Città del Vaticano 2006 (Documenti e riproduzioni, 7).

Conoscere la Biblioteca Vaticana, a cura di a. m. piazzoni e b. jatta, Città del Vaticano 2010.

Guida ai fondi manoscritti, numismatici, a stampa della Biblioteca Vaticana, a cura di f. d'aiuto e p. vian, I-II, Città del Vaticano 2011 (Studi e testi 466-467).

La Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana luogo di ricerca al servizio degli studi. Atti del convegno, Roma, 11-13 novembre 2010, a cura di m. buonocore e a. m. piazzoni, Città del Vaticano 2011 (Studi e testi 468).

Storia della Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Città del Vaticano 2010- :

- Le origini della Biblioteca Vaticana tra Umanesimo e Rinascimento (1447-1534), a cura di a. manfredi, 2010;

- La Biblioteca Vaticana tra Riforma cattolica, crescita delle collezioni e nuovo edificio (1535-1590), a cura di m. ceresa, 2012;

- La Vaticana nel Seicento (1590-1700): una biblioteca di biblioteche, a cura di c. montuschi, 2014;

- La Biblioteca Vaticana e le arti nel secolo dei lumi (1700-1797), a cura di b. jatta, 2016;

- La Biblioteca Vaticana dall'occupazione francese all'ultimo papa re (1797-1878), a cura di a. rita, 2020.